📰 Trending Topics

Google News - Trending

15 Players Trending Down (2026 Fantasy Baseball) - FantasyPros

2026-03-02 13:57

Google News - Technology

Apple Introduces Low-Cost iPhone 17e, Upgraded iPad Air - Investor's Business Daily

2026-03-02 21:02

- Apple Introduces Low-Cost iPhone 17e, Upgraded iPad Air Investor's Business Daily

- Apple introduces iPhone 17e Apple

- Apple launches cheaper iPhone 17e in push to boost iPhone sales CNN

- Apple debuts $599 iPhone 17e, more powerful iPad Airs Yahoo Finance

- Apple Debuts iPhone 17e and M4 iPad Air, Starting Product Wave Bloomberg

Galaxy S26 vs. S26+ vs. S26 Ultra: Everything You Need to Know About Samsung's 2026 Flagship Phones - PCMag

2026-03-03 09:11

- Galaxy S26 vs. S26+ vs. S26 Ultra: Everything You Need to Know About Samsung's 2026 Flagship Phones PCMag

- Samsung sneaks out a business Galaxy S26 Ultra and keeps the price the same TechRadar

- How to get Galaxy Buds 4 Pro for FREE during Galaxy S26 pre-order week 9to5Toys

- T-Mobile Is Offering the Samsung Galaxy S26 Ultra "On Us" With No Trade-In or Port-In Required IGN

- I spent a weekend traveling with the Galaxy S26 Ultra's Privacy Display – what you should know 9to5Google

Pokémon Pokopia is an expansive adventure disguised as a cozy life sim - The Verge

2026-03-02 13:00

- Pokémon Pokopia is an expansive adventure disguised as a cozy life sim The Verge

- Pokémon Pokopia Replaces Conflict With Creature Comforts The New York Times

- Pokémon Pokopia Review IGN

- Pokémon Pokopia Review - A Pleasant Paradise Game Informer

- Pokemon Pokopia Review - The Pokemon Anniversary Gift I Didn't Know I Wanted GameSpot

Samsung Wallet Launches Digital Home Key for Smart Door Locks - Samsung Global Newsroom

2026-03-02 13:00

- Samsung Wallet Launches Digital Home Key for Smart Door Locks Samsung Global Newsroom

- The smart lock standard that could replace your keys is finally here The Verge

- What is Aliro? Everything you need to know about the new smart home standard for locks ZDNET

- Samsung’s Digital Home Key will work with UWB and NFC smart locks 9to5Google

- Samsung’s Digital Home Key lets you use your phone as your key The Verge

Apple’s new products add C1X chip for three unique advantages - 9to5Mac

2026-03-02 21:19

- Apple’s new products add C1X chip for three unique advantages 9to5Mac

- Apple introduces the new iPad Air, powered by M4 Apple

- M4 iPad Air vs. Entry-Level iPad: Apple's Sneaky Upsell or Smart Upgrade? PCMag

- iPad Air M4 vs. iPad Air M3: The few new things in Apple's midrange tablet Engadget

- Apple launches a new iPad Air with an upgraded M4 processor The Verge

NASA - Breaking News

Smoke Rises Over Big Cypress National Preserve

2026-03-03 05:00

On February 22, 2026, a wildland fire was discovered in Big Cypress National Preserve, about 25 miles (40 kilometers) east of Naples, Florida. The blaze, dubbed the National fire, moved through dry vegetation and sent a plume of smoke billowing over parts of the preserve and nearby communities.

The MODIS (Moderate Resolution Imaging Spectroradiometer) on NASA’s Aqua satellite captured this image on the afternoon of February 25. By then, the fire had burned around 24,000 acres (9,700 hectares), according to the National Park Service.

After carrying smoke southward in previous days, winds shifted to start pushing it north by the time Aqua captured this image. According to news reports, the smoke reduced visibility and led to the brief closure of I-75—the interstate nicknamed “Alligator Alley” that runs east-west through the northern part of the preserve. It also contributed to smog over Lake Okeechobee.

The fire continued to spread over the next several days, reaching just over 35,000 acres (14,000 hectares) by February 28, according to InciWeb. As of March 2, it remained roughly the same size and was 38 percent contained.

The fire’s cause remains under investigation. Officials noted, however, that its spread was driven by ample fuel, including vegetation that was dry from persistent, extreme drought and damaged by recent frost. The National Interagency Fire Center’s wildland fire outlook calls for above-normal fire potential across Florida through May.

NASA Earth Observatory image by Lauren Dauphin, using MODIS data from NASA EOSDIS LANCE and GIBS/Worldview. Story by Kathryn Hansen.

References & Resources

- Big Cypress National Preserve (2026, February 27) News Releases. Accessed March 2, 2026.

- Gulf Coast News (2026, February 26) Alligator Alley reopens following smoke-related closure from Big Cypress National Preserve fire. Accessed March 2, 2026.

- Gulf Coast News (2026, February 26) Smoke from Big Cypress National Preserve fire shuts down Alligator Alley. Accessed March 2, 2026.

- Lake Okeechobee News (2026, February 27) Smoke from Big Cypress Preserve wildfire results in smog over Lake Okeechobee. Accessed March 2, 2026.

- National Integrated Drought Information System (2026, February 24) Florida. Accessed March 2, 2026.

- National Interagency Coordination Center (2026, March 2) Outlooks. Accessed March 2, 2026.

You may also be interested in:

Stay up-to-date with the latest content from NASA as we explore the universe and discover more about our home planet.

Smoke filled river valleys in northeastern Washington and parts of British Columbia.

Lightning likely ignited several large fires that sent smoke pouring over the Canadian province in early September 2025.

Blazes spread across Los Alerces National Park, home to some of the world’s oldest trees.

What’s Up: March 2026 Skywatching Tips from NASA

2026-03-02 20:45

A total lunar eclipse glows red, Venus and Saturn get close, and we ring in the vernal equinox

A total lunar eclipse blood moon takes centre stage, Venus and Saturn cozy up for a conjunction, and we celebrate the vernal equinox.

Skywatching Highlights

- March 3: Total Lunar Eclipse (Blood Moon)

- March 8: Venus + Saturn Conjunction

- March 20: Vernal Equinox

Transcript

A total lunar eclipse blood moon takes center stage, Venus and Saturn cozy up for a conjunction and we celebrate the vernal equinox.

That’s What’s Up this March.

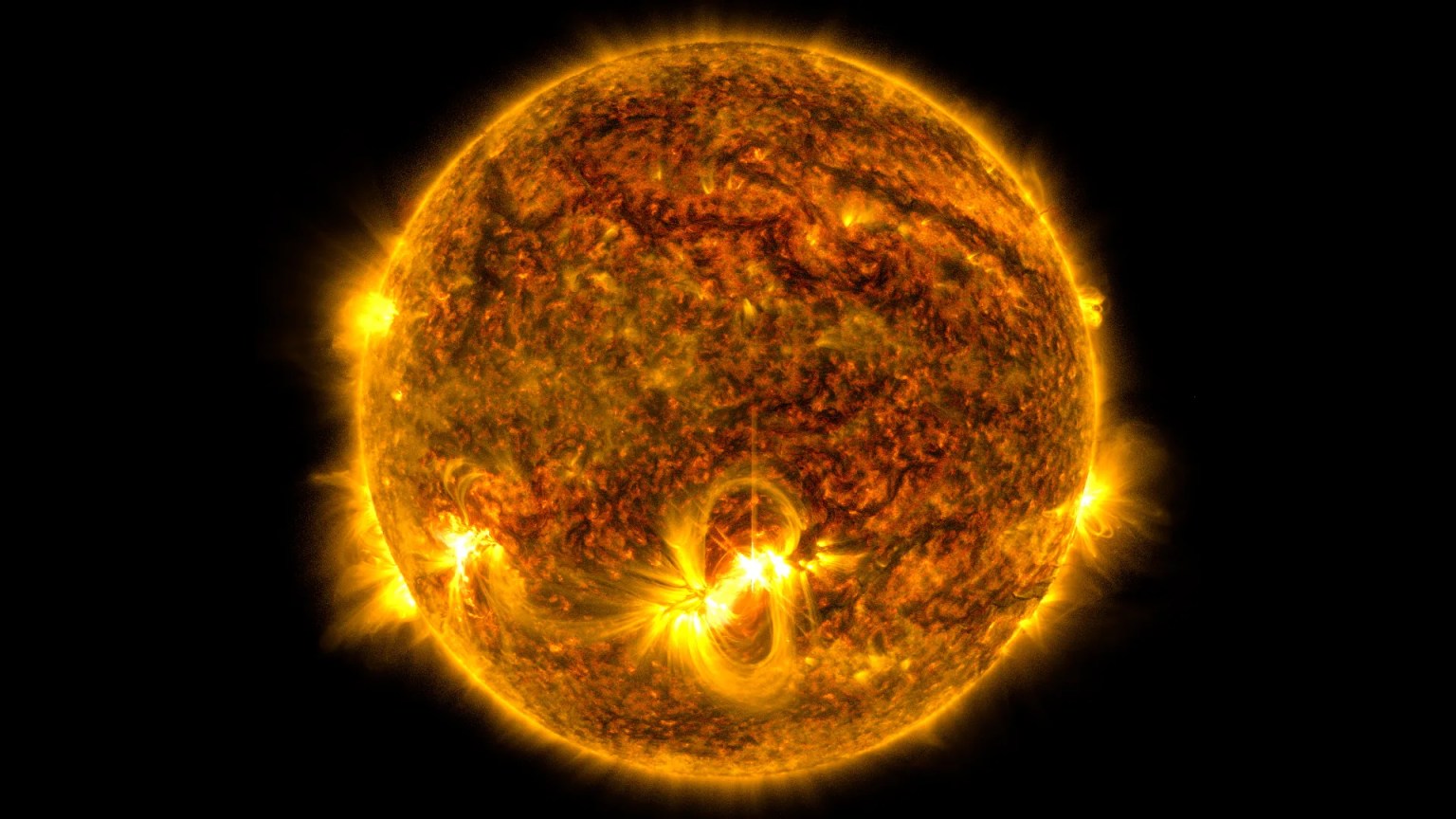

Is it Mars or is it the Moon? On March 3rd, a total lunar eclipse will turn the Moon bright red.

During a lunar eclipse, which can only happen during a full Moon, Earth passes between the Sun and the Moon, casting a shadow on the lunar surface.

During a partial lunar eclipse, the Moon moves only partially into the dark shadow, or umbra, cast by Earth.

But, during a full lunar eclipse, the Sun, Earth, and Moon are exactly aligned, leaving the Moon completely enveloped in Earth’s shadow.

When this happens, the Moon actually turns blood red.

While you might imagine a full lunar eclipse would leave the Moon completely dark, Earth’s atmosphere scatters the light, illuminating the Moon in this orange-reddish hue.

So look up and bask in the red glow of our lunar companion.

This full lunar eclipse will be visible from eastern Asia and Australia in the evening, from the Pacific at night, and from most of North and Central America as well as western South America in the early morning.

On March 8th, Venus and Saturn will cozy up for a conjunction in the evening sky.

The pair will be about one degree apart, which is roughly the width of a single finger if you hold it at arm’s length.

A conjunction happens when two objects in the night sky appear close together, even if they’re far apart in space. In reality, Venus and Saturn are nearly a billion miles apart!

But to see the pair get close in the sky from our perspective, look close to the horizon in the western sky just after sunset.

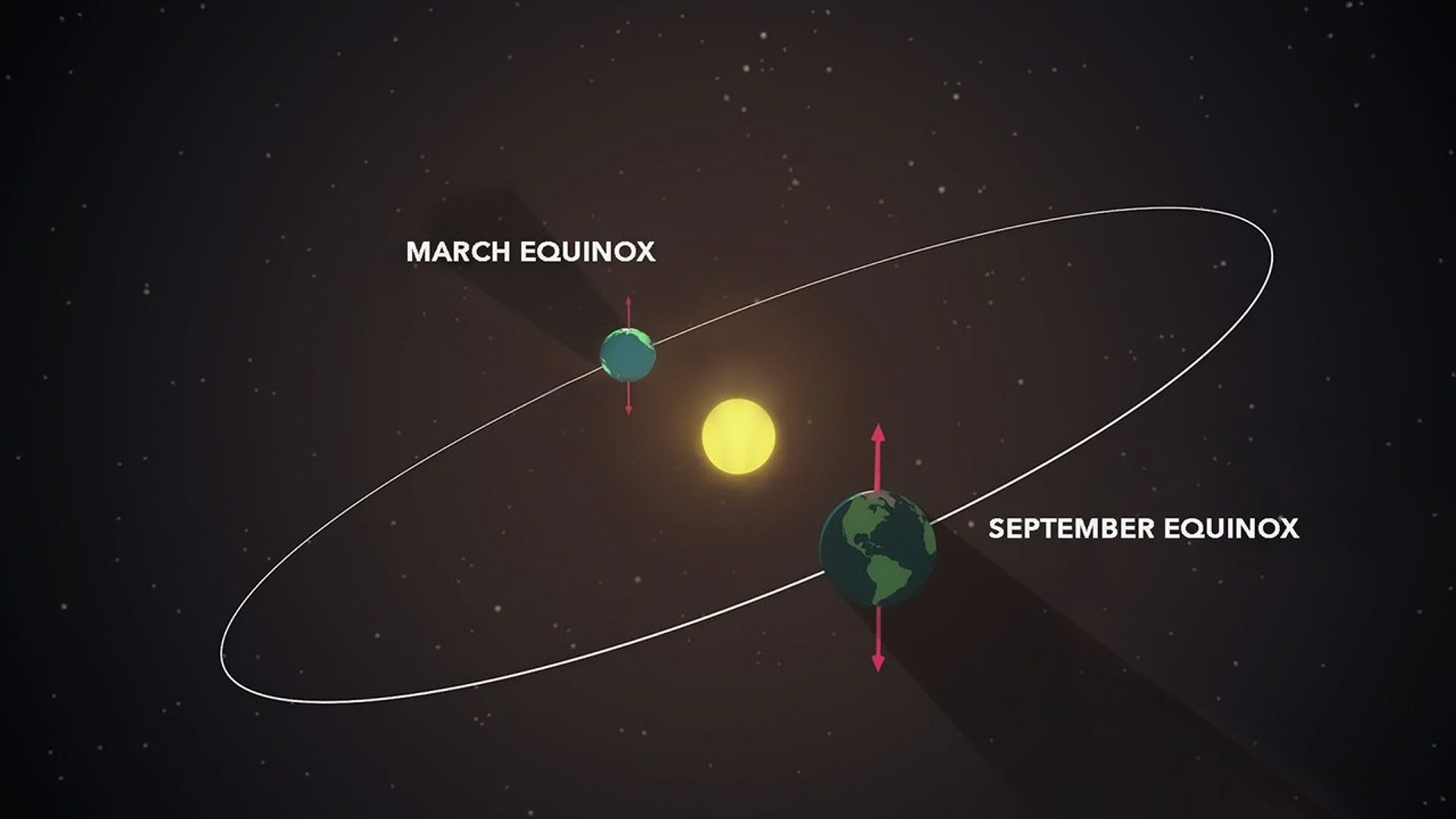

On March 20th, we ring in the vernal equinox, marking a transition into the next season.

While this is colloquially known as the first day of spring in the northern hemisphere and the first day of autumn in the southern hemisphere, astronomically this equinox occurs when the Sun crosses above Earth’s equator while traveling from south to north.

On this day, northern and southern hemispheres experience roughly equal amounts of sunlight and day and night are also about equal, each lasting almost exactly 12 hours.

So enjoy the start of a new season with a day of perfectly balanced sunlight.

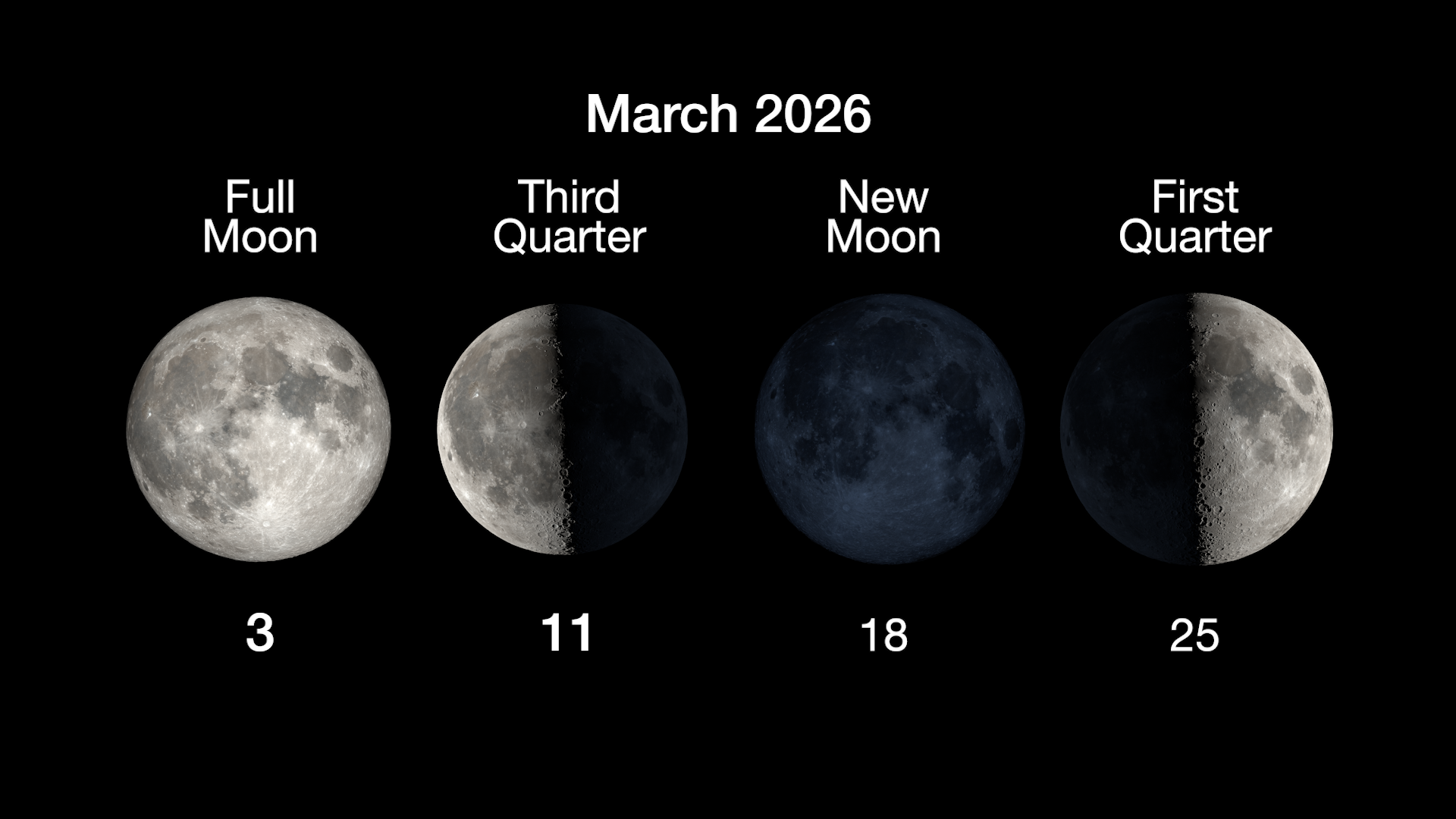

Here are the phases of the Moon for March.

You can stay up to date on all of NASA’s missions exploring the solar system and beyond at science.nasa.gov.

I’m Chelsea Gohd from NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory, and that’s What’s Up for this month.

Sunglint on Atlantic Ocean

2026-03-02 16:54

Sunlight beams off a partly cloudy Atlantic Ocean just after sunrise as the International Space Station orbited 263 miles above on March 5, 2025. This is an example of sunglint, an optical phenomenon that occurs when sunlight reflects off the surface of water at the same angle that a satellite sensor views it. The result is a mirror-like specular reflection of sunlight off the water and back at the satellite sensor or astronaut.

While sunglint often produces visually stunning images, the phenomenon can create problems for remote sensing scientists because it obscures features that are usually visible. This is particularly true for oceanographers who use satellites to study phytoplankton and ocean color. As a result, researchers have developed several methods to screen sunglint-contaminated imagery out of data archives.

Despite the challenges posed by sunglint, the phenomenon does offer some unique scientific opportunities. It makes it easier, for instance, to detect oil on the water surface, whether it is from natural oil seeps or human-caused oil spills. This is because a layer of oil smooths water surfaces.

Text credit: Adam Voiland

Image credit: NASA

NASA, JAXA to Cover HTV-X1 Spacecraft Departure from Space Station

2026-03-02 16:50

After delivering about 12,000 pounds of supplies, scientific investigations, hardware, and other cargo to the International Space Station for NASA and its international partners, JAXA’s (Japan Aerospace Exploration Agency’s) uncrewed HTV‑X1 cargo spacecraft is scheduled to depart Friday, March 6.

Watch NASA’s live coverage beginning at 11:45 a.m. EST on NASA+, Amazon Prime, and the agency’s YouTube channel in advance of the spacecraft’s release at 12 p.m. Learn how to watch NASA content through a variety of online platforms, including social media.

On Thursday, March 5, flight controllers will use the space station’s Canadarm2 robotic arm to detach HTV-X1 from the Harmony module’s Earth-facing port on the station and maneuver it into position for release. NASA will not provide live coverage of the spacecraft’s detachment from the orbiting laboratory. NASA astronaut Chris Williams will monitor HTV-X1’s systems during undocking and departure.

The HTV-X1 spacecraft will remain in orbit for more than three months acting as a scientific platform for JAXA’s experiments. Following the deorbit command, the spacecraft will dispose of several thousand pounds of trash during re-entry into Earth’s atmosphere, where it will burn up harmlessly.

The spacecraft arrived at the space station on Oct. 29, 2025, after launching Oct. 25 on an H3 rocket from Japan’s Tanegashima Space Center.

For more than 25 years, people have lived and worked continuously aboard the International Space Station, advancing scientific knowledge and making research breakthroughs that are not possible on Earth. The space station is a critical testbed for NASA to understand and overcome the challenges of long-duration spaceflight and to expand commercial opportunities in low Earth orbit. As commercial companies concentrate on providing human space transportation services and destinations as part of a strong low Earth orbit economy, NASA is focusing its resources on deep space missions to the Moon as part of the Artemis campaign in preparation for future astronaut missions to Mars.

Get breaking news, images and features from the space station on Instagram, Facebook, and X.

Learn more about International Space Station research and operations at:

-end-

Josh Finch / Jimi Russell

Headquarters, Washington

202-358-1100

joshua.a.finch@nasa.gov / james.j.russell@nasa.gov

Sandra Jones

Johnson Space Center, Houston

281-483-5111

sandra.p.jones@nasa.gov

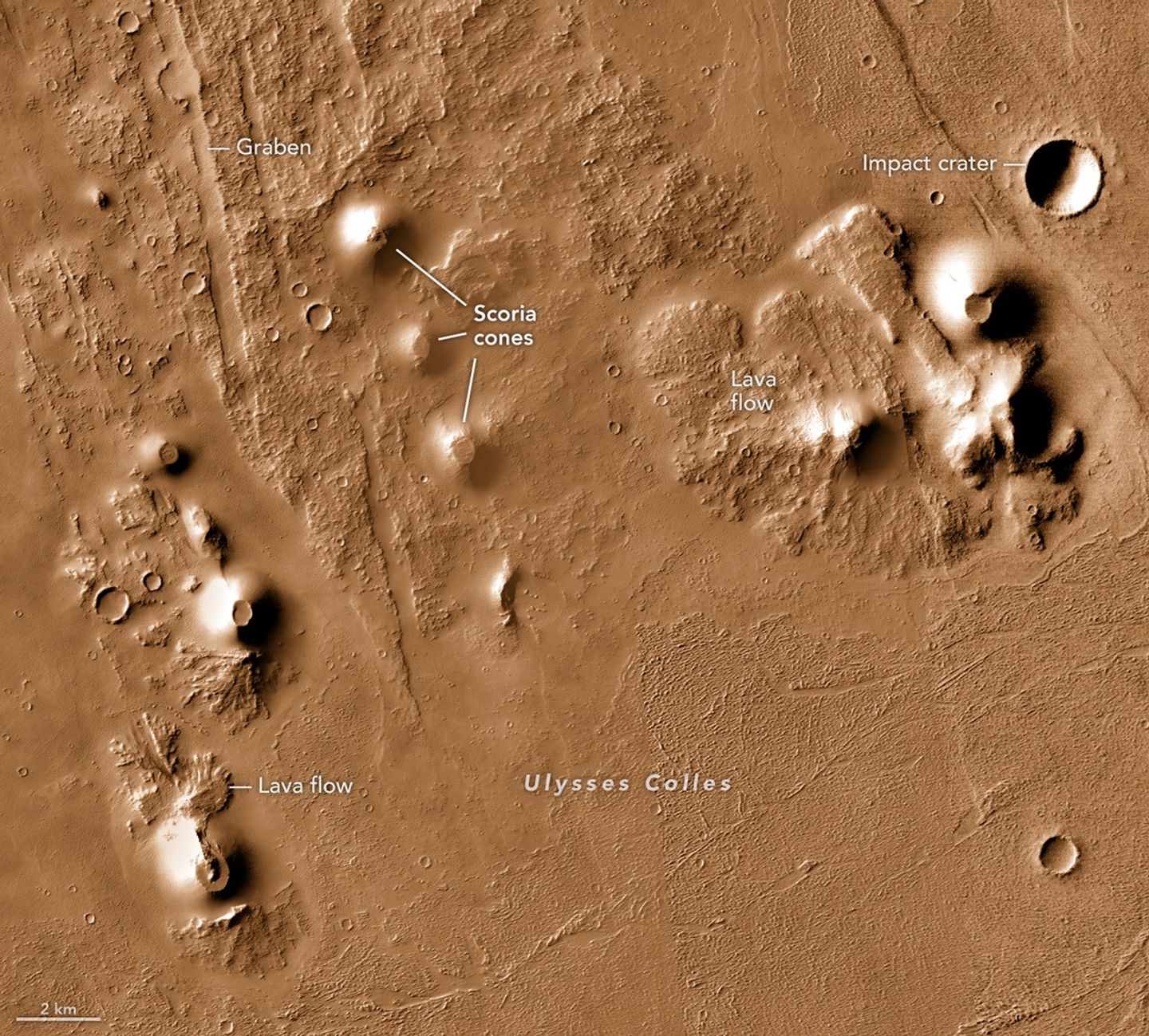

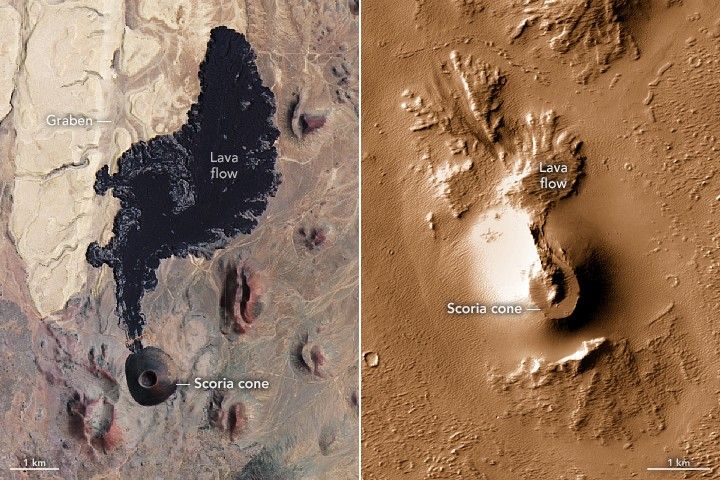

Scoria Cones on Earth and Mars

2026-03-02 05:01

Since the 1970s, planetary geologists have known that volcanic features cover large swaths of Mars. Early Mariner 9 images revealed massive shield volcanoes and lava plains on a scale unlike anything on Earth. Olympus Mons, the tallest volcano in the solar system, stands nearly three times higher than Mount Everest. Alba Mons, the planet’s widest volcano, spans a distance comparable to the length of the continental United States.

Both Olympus Mons and Alba Mons were primarily built by basaltic effusive eruptions—relatively calm outpourings of “runny” lavas that spread across the surface in sheets. This is thought to be the most common type of volcanism on Mars, accounting for the vast majority of its volcanic landforms. However, a small portion was produced by explosive volcanism of the sort that forms volcanic cones, pyroclastic flows, and ashfalls.

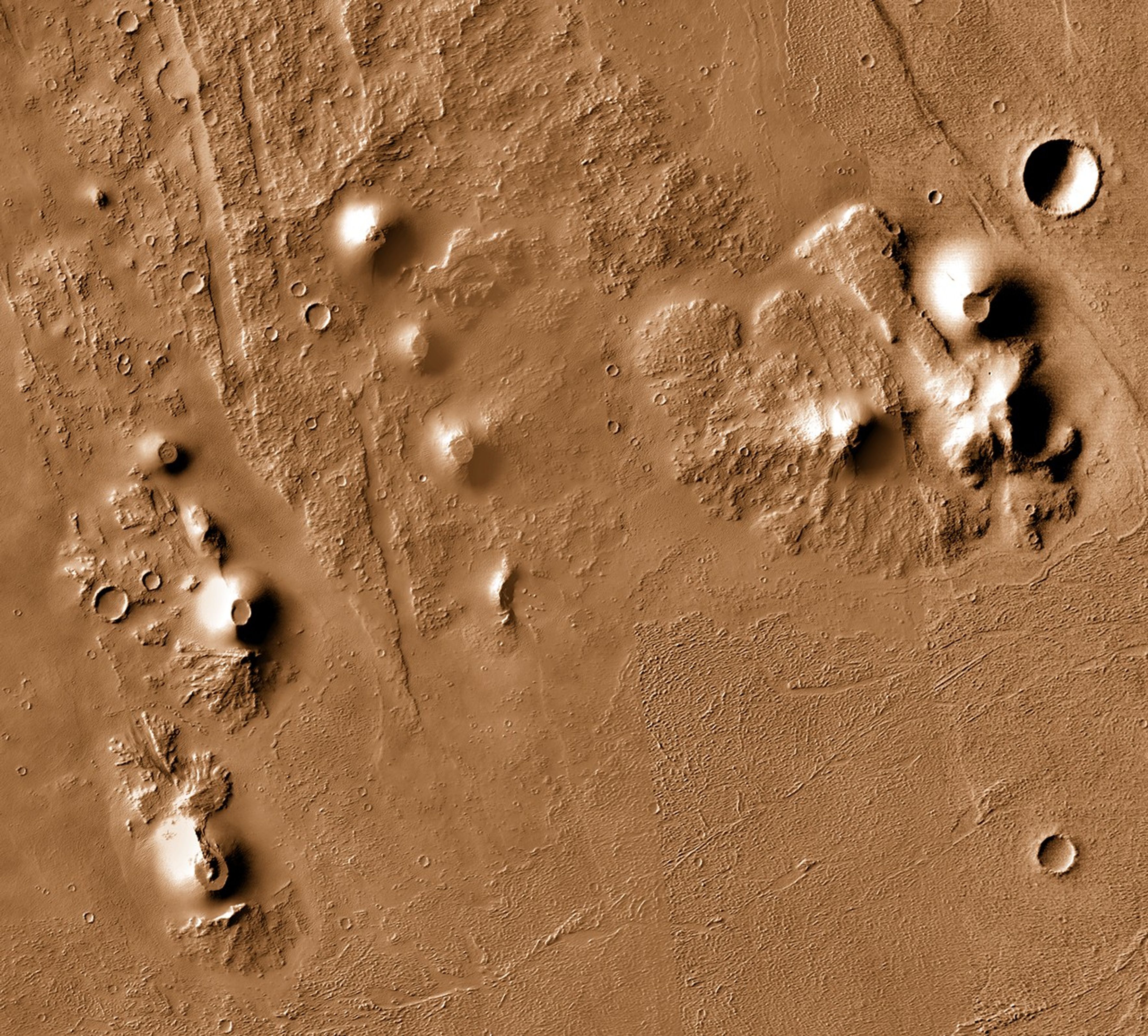

The dearth of explosive volcanic features on Mars has long puzzled geologists. With an average atmospheric pressure 160 times lower than Earth’s and only a third of the gravity, explosive eruptions should theoretically occur more easily on the Red Planet, said Petr Brož, a planetary geologist with the Czech Academy of Sciences. That rarity is part of what makes features like the volcanic cones (shown above) found in Mars’ Ulysses Colles region so compelling to planetary geologists.

“They appear to be scoria cones—a clear sign of explosive volcanism,” Brož added. “They were the first identified in the Tharsis region in the 2010s, and they helped paint a broader and more complete picture of Martian volcanism.”

The CTX (Context Camera) on NASA’s Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter captured this image (second image above) of Ulysses Colles above on May 7, 2014. Ulysses Colles is located at the southern edge of Ulysses Fossae, a group of troughs within the Tharsis volcanic region.

The OLI (Operational Land Imager) on Landsat 8 captured an image with similar cones in the San Francisco Volcanic Field (SFVF) in northern Arizona on June 19, 2025 (top). Planetary geologists consider the cones in the two locations to be highly analogous. Both images also include grabens—linear blocks of crust that have shifted downward.

In both images, the scoria cones appear as rounded hills crowned with circular vents, while lava flows spread outward as dark, textured areas around the bases of the cones. At both locations, seemingly younger and smaller lava flows appear to spill from some cones, while older, more weathered flows lie in the background.

“Understanding similar features on Earth helps us know what to look for on Mars and interpret processes that we can’t observe directly,” said Patrick Whelley, a NASA volcanologist who is part of a team that develops field equipment and techniques for Moon and Mars exploration.

SP Crater (above left), located in Arizona’s San Francisco Volcanic Field, features a 7-kilometer-long lava flow that extends northward and has been used for NASA astronaut geology training. In two places, the flow has spilled into a graben, creating a distinctive half-moon pattern along its left side.

On Earth, scoria cones form when gas-rich magmas soar high into the air and solidify into small particles of material called scoria that accumulate in steep-sided structures. While similar processes create cones on Earth and Mars, there are important differences. Martian scoria cones are typically taller, wider, and have gentler slopes, Flynn said. That makes sense. With lower gravity and atmospheric pressure, volcanic fountains can loft erupted magma higher and farther from the vent, producing larger cones.

There are far more scoria cones on Earth, where tens of thousands exist and account for about 90 percent of volcanoes on land. On Mars, “we have only identified tens to a few hundred candidates,” Broz said. It could be that explosive volcanism was never common on Mars, or it could be that it was but that explosive features have been covered up by younger, effusive flows or destroyed by erosion, he added.

Whelley noted that on Mars, it remains unclear whether the Martian lava flows or the scoria cones formed first. The lava flow could be older, with the cone forming on top. Or, the cone may have formed first and later become plugged, forcing lava to spill from its side. Determining the order of events is one of the “puzzles of geology” that planetary geologists try to solve when studying Martian features remotely, he said. “Visiting places like the San Francisco Volcanic Field and studying the geology of analogous features up close on Earth helps us know what clues to look for when interpreting Martian geology.”

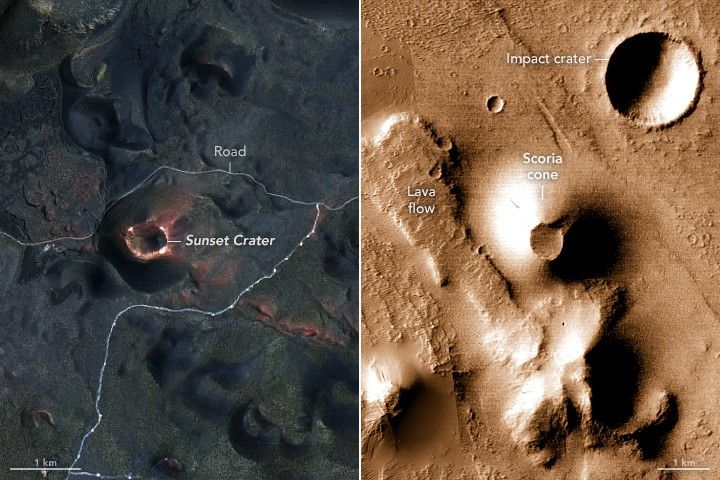

Below (left) is a closer view of a scoria cone on Earth, southeast of SP Crater, called Sunset Crater. It erupted about 800 years ago, making it the youngest scoria cone in the San Francisco Volcanic Field. The analogous cone in Ulysses Colles (right), in contrast, is thought to be billions of years old.

Note that eruptions that create scoria cones are “mildly explosive,” usually Strombolian events, characterized by intermittent lava fountains, said Ian Flynn, a planetary geologist at the University of Pittsburgh. They differ from the far more violent explosive eruptions that send ash columns billowing tens of kilometers into the air, as happened at Hunga Tonga-Hunga Ha’apai in the South Pacific, he added.

Mars also shows evidence of highly explosive “super eruptions,” but that type of eruption leaves behind a different geologic signature: large depressions called paterae and broad, thin deposits of ash and other erodible material sculpted into landforms such as yardangs.

Planetary comparison is valuable for understanding the geology of distant worlds, Brož said. Without such comparisons, it becomes harder to determine how landforms on other planets or moons may have formed at all.

But caution is essential. “In planetary science, it’s often said—only half-jokingly—that even if something looks like a duck, behaves like a duck, and sounds like a duck, it may not actually be a duck,” he added. It’s easy, for instance, to confuse scoria cones with mud volcanoes.

Researchers are highly confident that the Ulysses Colles cones formed through explosive volcanism based on the surrounding volcanic landscape, but in more ambiguous terrain it can be difficult to tell. Mars is fundamentally different from Earth, he cautioned. Brož’s laboratory research suggests, for instance, that mud flows on Mars can look much like certain types of lava flows, and that, under certain conditions, they can even boil and levitate. “We also have to avoid being constrained by terrestrial experience,” he said. “If we fail to think outside the box, we may overlook important possibilities.”

NASA Earth Observatory images by Lauren Dauphin, using Landsat data from the U.S. Geological Survey and CTX data from the Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter. Story by Adam Voiland.

References & Resources

- Brož, P. Everything you wanted to know about Martian scoria cones, but were afraid to ask. Accessed February 27, 2026.

- Brož, P., et al. (2021) An overview of explosive volcanism on Mars. Journal of Volcanology and Geothermal Research, 409(15), 107125.

- Brož, P., et al. (2014) Shape of scoria cones on Mars: Insights from numerical modeling of ballistic pathways. Earth and Planetary Science Letters, 401(15), 14-23.

- Brož, P. & Hauber, E. (2012) A unique volcanic field in Tharsis, Mars: Pyroclastic cones as evidence for explosive eruptions. Icarus, 218(1), 88-99.

- Eos (2021, May 7) Tiny Volcanos Are a Big Deal on Mars. Accessed February 27, 2026.

- Gullikson, A. (2021) A Geologic Field Guide to S P Mountain and its Lava Flow, San Francisco Volcanic Field, Arizona. Accessed February 27, 2026.

- Mouginis-Mark, P. (2022) Martian volcanism: Current state of knowledge and known unknowns. Geochemistry, 82(4), 125886.

- NASA (2026) Planetary Analog Explorer. Accessed February 27, 2026.

- NASA Planetary Analogs. Accessed February 27, 2026.

- NASA Planetary Analogs: News & Features. Accessed February 27, 2026.

- NASA Earth Observatory (2018, October 9) Flood Basalts on Earth and Mars. Accessed February 27, 2026.

- U.S. Geological Survey Astrogeology Science Center (2021, August 31) S P Mountain Field Guide. Accessed February 27, 2026.

- U.S. Geological Survey San Francisco Volcanic Field. Accessed February 27, 2026.

- Richardson, J.A., et al. (2021) Small Volcanic Vents of the Tharsis Volcanic Province, Mars. Accessed February 27, 2026.

- Whelley, P., et al. (2021) Stratigraphic Evidence for Early Martian Explosive Volcanism in Arabia Terra. Geophysical Research Letters, 48(15), e2021GL094109.

You may also be interested in:

Stay up-to-date with the latest content from NASA as we explore the universe and discover more about our home planet.

A group of satellites with interferometric synthetic aperture radar makes it possible for geologists to detect how much and where…

A landmass that was once encased in the ice of the Alsek Glacier is now surrounded by water.

From Alaska’s Saint Elias Mountains to Pakistan’s Karakoram, glaciers speed up and slow down with the seasons.

TechCrunch - Latest

Cursor has reportedly surpassed $2B in annualized revenue

2026-03-03 01:53

India’s Pronto formalizes house help as its valuation jumps 8x in under a year

2026-03-03 01:15

ChatGPT uninstalls surged by 295% after DoD deal

2026-03-03 00:03

Stripe wants to turn your AI costs into a profit center

2026-03-02 23:18

Geopolitical drama reportedly stalls IPO of SoftBank-backed PayPay

2026-03-02 23:01